CANADA – October 1 marked an important day for Alberta. It’s when the province officially moved away from a single 10 per cent tax rate on personal income to a system with five separate brackets. Rates will increase on incomes over $125,000 and the top marginal rate will increase by 50 per cent.

This is yet another major blow to Alberta’s investment climate, further eroding the province’s competitiveness. Put simply, as the province struggles with a global decline in commodity prices (particularly regarding oil and gas), provincial government policies are making things worse.

Not long ago, Alberta was a beacon for prosperity in Canada. Its competitive tax regime created healthy competition within the federation and provided an example for other provinces to follow. While many provinces caught up over the years, Alberta has been moving backwards. Its tax increases have ended an already eroded tax advantage, which will make it more difficult to attract the labour and investment required to drive economic growth.

Up until October 1, Alberta had the lowest top combined federal-provincial (or state) income tax rate among Canadian provinces and U.S. states. Indeed, Alberta’s rate was lower than every U.S. state, even those without their own income taxes since the top U.S. federal rate is 39.6 per cent. (The top federal rate in the U.S., however, kicks in at a much higher income level than in Canada.) Alberta will now have a higher top marginal rate than competing energy-producing jurisdictions in the U.S. including Texas, Alaska and Wyoming – all of which have no state income tax.

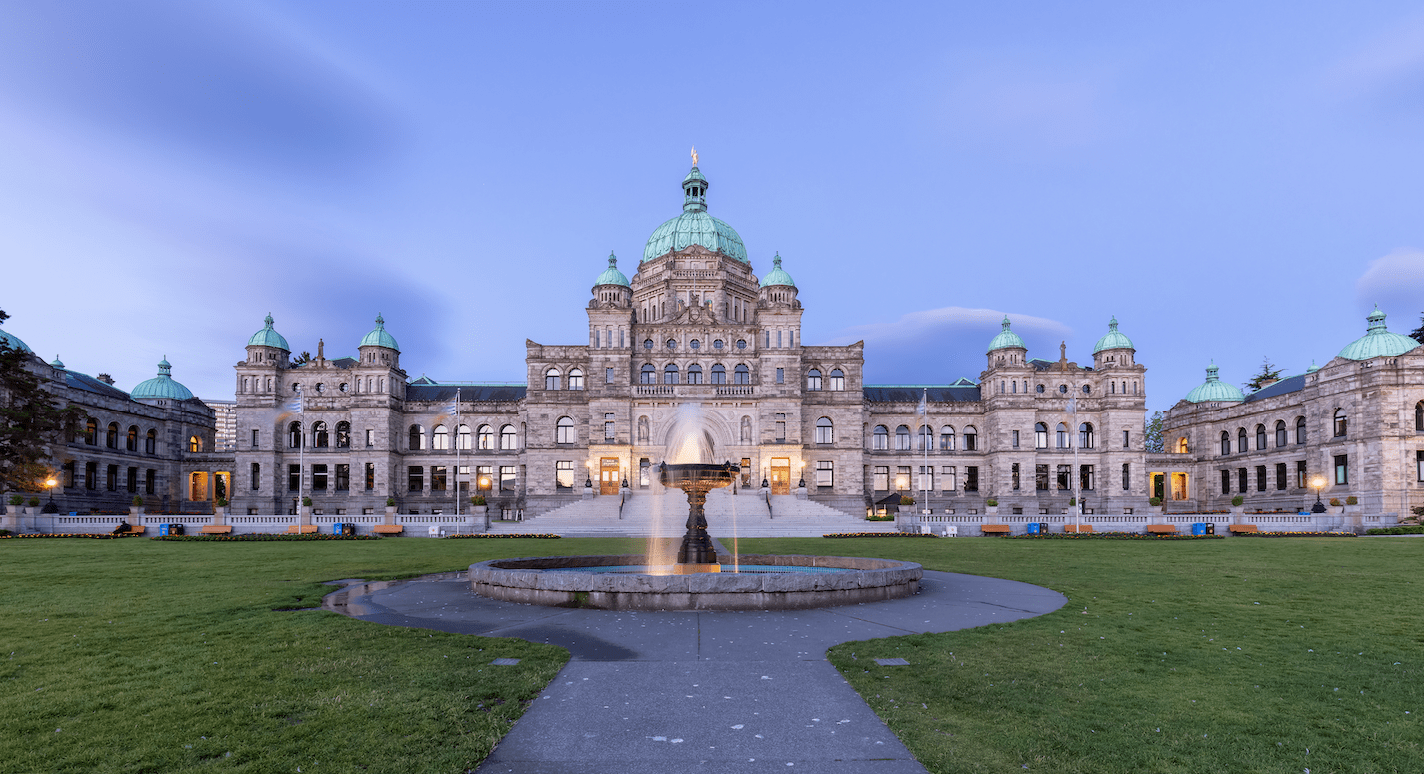

Not only is Alberta’s tax advantage against many U.S. states gone, but Alberta’s top marginal rate will be tied with Saskatchewan’s (44 per cent) and slightly above B.C.’s rate (43.7 per cent) as of next year. So much for the Alberta Advantage.

Taxes certainly aren’t the only consideration for determining a jurisdiction’s competitiveness, but high and increasing rates will hamper Alberta’s ability to attract and retain skilled workers and entrepreneurs, and its ability to encourage investment. On the issue of tax rates and incentives, there’s general agreement. Consider, for instance, the recent words of a federal politician explaining the challenges posed by increasing taxes on highly skilled workers:

“On the question of personal income tax increases, we are firmly opposed to them. Look at a province like New Brunswick. They will have a tax rate of 58.75 per cent. Now New Brunswick doesn’t have a medical faculty. How is New Brunswick going to be able to attract and retain top level medical doctors when they’re going to be told, ‘Oh, by the way, our tax rate is now going to be close to 60 per cent?’ ”

Premier Rachel Notley might be surprised to learn that this analysis comes from her federal NDP counterpart Thomas Mulcair. The logic of Mulcair’s comment certainly applies to Alberta. After all, as an energy producing province, Alberta has to compete directly with some of the lowest tax jurisdictions in North America for labour and investment.

And the weight of economic evidence supports Mulcair’s claim. High and increasing marginal tax rates change people’s behaviour by discouraging them from doing economically productive things like saving, investing and taking entrepreneurial risks. They also erode the tax base and encourage the use of loopholes to reduce one’s tax liability.

But it’s not just personal income tax increases that will reduce Alberta’s competitiveness. The government has advanced a suite of policies that give potential residents and investors pause when thinking about Alberta as destination for work and investment. This includes the additional burden of a 20 per cent corporate tax increase, the uncertainty of a royalty review, an increasing minimum wage, the potential for new environmental regulations, ongoing budget deficits and the prospect of further tax increases.

Alberta’s former tax advantage allowed it to grow and prosper like no other province. Ending it will hinder the province’s return to robust growth. It’s the wrong time to bury the Alberta Advantage.

– Steve Lafleur is a senior policy analyst and Charles Lammam is director of fiscal studies at the Fraser Institute.

© 2015 Distributed by Troy Media