David Elstone, Management Consultant at spartreegroup.com

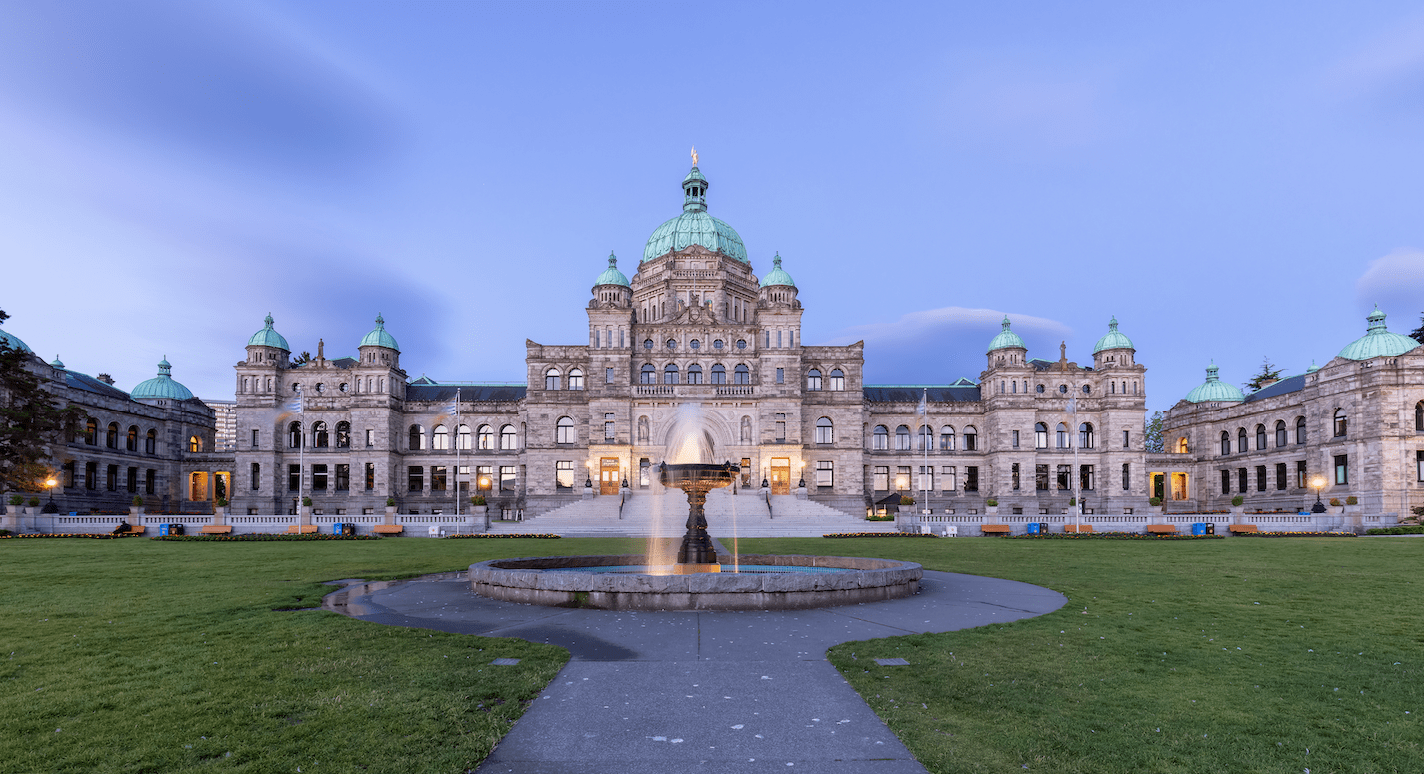

An Editorial Opinion – View From The Stump, April, 2024

BRITISH COLUMBIA – Premier Eby and his Ministers Ralston and Mercier are often heard saying “more jobs from trees harvested” when talking about the BC forest industry.

Such a phrase resonates easily with the public as a common-sense vision for the British Columbia forest sector, the essence of which has also become part of the NDP government’s official industrial policy for the forest sector.

Indeed, the Province has recently published a policy guidance document, Clean and Competitive: A Blueprint for BC’s Industrial Future confirming the BC government’s industrial policy for the forest sector as “encouraging and supporting the forest industry to move from the export of minimally processed timber, and towards advanced timber manufacturing” which “creates more jobs for people using less fibre than the traditional forest industry.”

To paraphrase the Blueprint’s forestry related comments, the Province views “minimally processed materials”, (aka dimensional lumber), as limiting the number of jobs and opportunities and leaves the industry all that more exposed to market conditions.

As implied in Blueprint, the motivation for transitioning to “advanced timber manufacturing” or in other words, value-added wood products manufacturing is to help offset job losses that the sector has experienced due to the impacts of the mountain pine beetle epidemic on timber supply.

While there are many points to take aim at in the Province’s view of “minimally processed timber” and the reasons for job losses in the forest sector, I will focus my commentary on why I believe the transition so far to value-added has been slow and the attention on more jobs has been an ineffective in driving the Province’s desired change.

What does “more jobs from trees harvested” mean to manufacturers (and their investors)? To be honest, absolutely nothing. It does not send a signal about surety and stability of fibre supply or about the province’s attitude on hosting conditions. More jobs is a nice political slogan, but sounds increasingly misguided as an expectation, especially when current forestry jobs are being lost in the thousands. As rational economic entities, manufacturers (small and big) do not strategize to increase jobs as an objective, rather they invest to minimize costs and maximize returns – sometimes that adds jobs and sometimes it eliminates them.

It is my sense that the BC government is frustrated with progress so far in fulfilling a vision of moving from a volume-oriented to value focused manufacturing. Efforts so far to promote value added manufacturing have largely been to help existing businesses to sustain themselves with equipment upgrades. A wave of widespread transformation has not occurred.

HISTORY: The creation of a mass timber manufacturing sector is viewed by the BC government as an opportunity to cause that desired wave of transformation. While I have applauded the efforts on promoting mass timber construction in BC, the notion of fostering demand to drive a shift/increase in manufacturing actually goes against the grain of history. The establishment of forest products manufacturing in this province has always been a supply-side driven story:

- The genesis of industrial lumber production came from the perspective of having untapped forests.

- Pulp production expanded largely from the ample supply of residual chips generated by sawmills.

- OSB production came from Aspen, a tree species at that time with little other commercial use in the province.

- Pellets came from sawdust and other sawmill by-products as well as harvesting residuals from interior forests.

- Even the coastal BC remanufacturing sector was essentially premised on a supply of primary product (lumber) which could be further processed and sold at profit (in essence, true “value added” from a manufacturing perspective).

While these are broad stroke generalizations, the point is that none of the major forest product segments were initiated from the demand side alone, but rather they were sparked by a preponderance of cost-competitive supply mixed with ingenuity and marketing savvy. Supply side market forces shaped the BC forest products manufacturing base along with the influences of the Manufactured Forest Products Regulation under the Forest Act.

MASS TIMBER: Ok, but there is growing demand for mass timber products and the BC forest industry produces plenty of the primary raw input, seven billion board feet of lumber in 2023. This should be a natural fit.

The answer is so far reflected by minimal uptake on mass timber manufacturing from existing lumber producers. Aside from Kalesnikoff Lumber which built their own mass timber manufacturing capacity (with a third line under construction) as an add-on to their sawmill and Mercer International which bought the Structurlam assets, there have been no other major players stepping up (for cross laminated timber or “CLT”).

With primary manufacturing facing challenges in securing logs just to run their mills, the dark cloud of uncertainty is a significant deterrent for anyone considering investing in BC for mass timber. Switching to mass timber production is not going to solve that problem.

Should existing lumber producers invest in mass timber manufacturing at the back end of their sawmill, following the Kalesnikoff model? It is really a question of market displacement, something that is not easy to do.

While the consumer benefits of mass timber are widely discussed, discussions are limited regarding the challenges with manufacturing. Making and marketing mass timber products is not so straightforward. Selling mass timber products is a drawn-out process, requires a suite of various types of support professionals (architects, engineers, project managers etc.) and is well beyond the scope of simply producing lumber, selling it to wholesalers or lumber yards and loading it onto a truck or railcar.

There is minimal incentive to shift to mass timber manufacturing, if demand for what you already produce, (lumber), is sufficient. Mass timber is not typically used in single-family housing starts, instead builders use dimensional framing lumber, (you know, that minimally processed timber we make in BC). For the US, single-family starts dominate residential construction and are increasing (unlike US multi-family starts).

One driver for a switch to producing mass timber might be higher financial returns in comparison to lumber; however, rarely are margins discussed publicly for value-added. I suspect the differential is not huge enough (or the risks are that much greater) to incentivize a decision to shift, because if it was, more operators would likely move into the space.

The Province claims that value-added manufacturing is less subject to the whims of market conditions. It is a curious point given that European imports of mass timber products are rumoured to be used even in this province’s construction projects. Furthermore, two of the largest mass timber manufacturers, in North America, Structurlam and Katerra have both found themselves in financial distress, and subsequently were purchased by Mercer International.

A prospective independent mass timber manufacturer without ties to an existing sawmill would need to buy its lumber supply at market prices, which means they must disrupt established sawmill-customer relationships. That’s not an easy hurdle to overcome. And of course, timber supply and lumber production are forecast to continue declining in BC, which will mean less lumber.

Unfortunately, that’s a cold splash of reality which is not meant to be a rebuttal on mass timber manufacturing, but rather an explanation of the state of things that also could apply to other value-added segments. How can these challenges be overcome?

POTENTIAL SOLUTIONS: An industrial policy to increase value-added manufacturing would be more effective if it considered the following:

- Acknowledge that successful secondary manufacturing growth rides on a healthy primary manufacturing sector by addressing fibre supply challenges and changing the current negative narrative. Period.

- Define what is meant by “higher value” manufacturing” and “advanced timber manufacturing” as there are various forms of secondary manufacturing. Many primary producers would argue that they make value-added products as well. Industry’s understanding of value-added manufacturing is something entirely different from the BC government’s. Everyone has to get on the same page.

- Recognize the different types of value-added manufacturers. Some may only rent a manufacturing facility (i.e., a custom cut sawmill) for a short period of time but still generate economic benefits for the sector. BCTS’ Value-Added Program with 700,000 m3/yr is insufficient to support a transformation and it limits the type of value-added players that can participate.

- Specify measurable targets for both wood products manufacturing and jobs.

- Most importantly, add the notion of sector competitiveness supported by an economic plan as industrial policy. The BC government needs to collaborate to shed the reputation of being the highest cost forest products manufacturing jurisdiction in North America. If not addressed, mills will continue to close. Conversely, improved competitiveness will bring more jobs and if guided correctly, more higher value manufacturing.

Just imagine if Premier Eby were to say, “hey we want more jobs from trees harvested by helping to create the most competitive and productive forest sector in the world!”… now that would change the conversation to one which the industry and its investors could relate.

This article was originally published in the April 2024 edition of the View From The Stump.