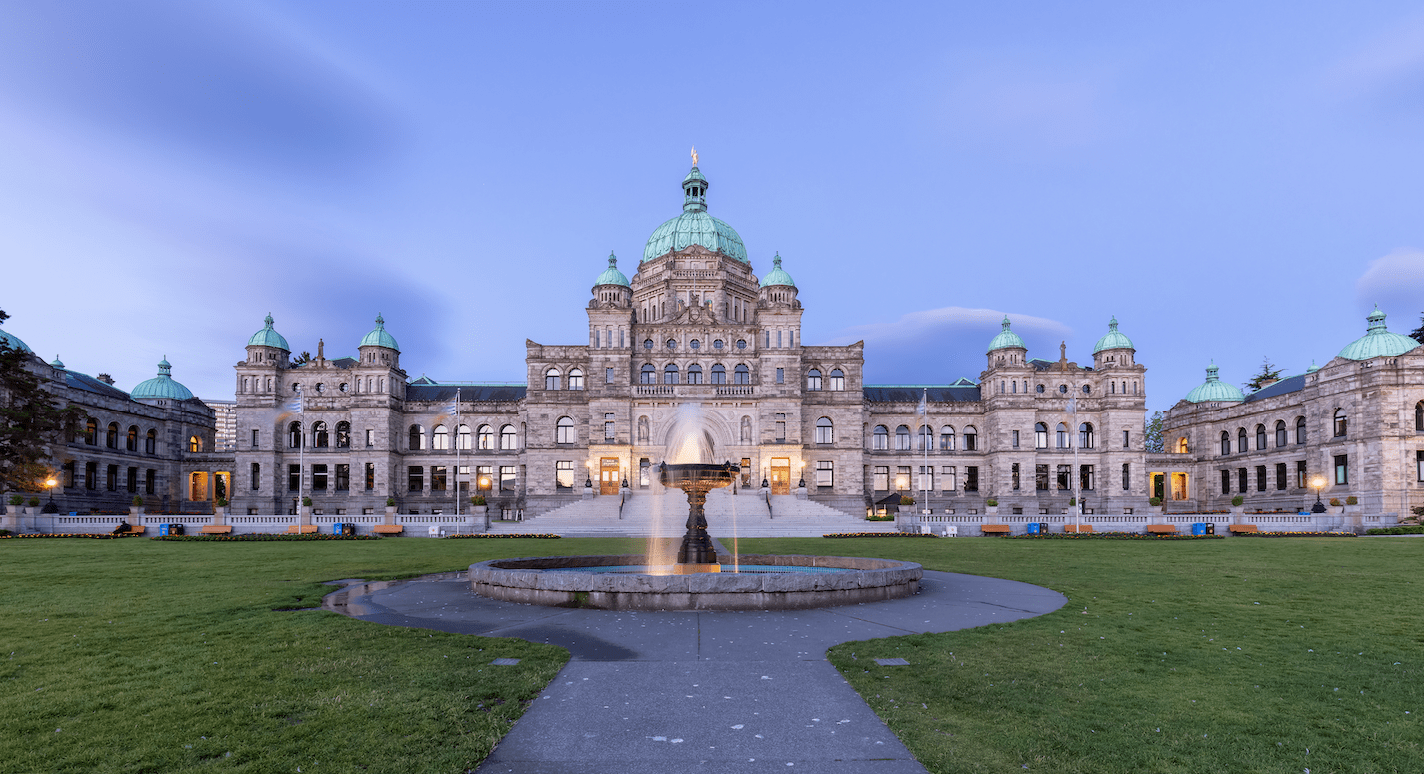

BC Government Scores at Bottom of the Class

BILL ROBSON

CANADA – Canada’s senior governments raise and spend huge amounts, and have legally unlimited capacity to borrow when their expenses exceed their revenues. Holding public officials accountable for their spending, taxing and borrowing is a foundational task in a system of representative government. Citizens have the right to know, and elected representatives have duties to them.

While much of the financial information presented to legislators and the public by Canada’s federal, provincial and territorial governments has improved over time, the C.D. Howe Institute’s 2022 report card reveals shortfalls. Too many governments present information that is opaque, misleading and late.

This report card on the usefulness of governments’ budgets, estimates and financial statements assigns letter grades that reflect how readily an interested but non-expert user can find, understand and act on the information they should contain. In this year’s report card – which covers year-end financial statements for fiscal year 2020/21, and budgets and estimates for 2021/22 – Alberta and Yukon topped the class with grades of A and A- respectively. Nunavut, Saskatchewan, and New Brunswick each scored B+, Ontario scored a B, and Quebec scored a B-. Prince Edward Island scored a C+, and Nova Scotia scored a C. The federal government and Newfoundland and Labrador got grades of D+. Manitoba, British Colombia and the Northwest Territories were at the bottom of the class with grades of D.

In some respects, this mixed picture represents improvement. Two decades ago, none of Canada’s senior governments budgeted and reported revenues, expenses and surpluses or deficits on the same accounting basis; today, presentations consistent with public sector accounting standards are the rule. Canada’s governments, however, can do better.

The Northwest Territories could improve its grade with better budget presentations and interim updates. Alberta could improve its grade by releasing its estimates in one document. Newfoundland and Labrador could improve its grade with a more timely release of its budget and estimates. Most senior governments could improve their grades with more timely releases of public accounts: only two – Alberta and Saskatchewan – released theirs within 90 days of the end of the fiscal year. The federal government, which earned a grade of F in last year’s report card, mainly because of its egregious and unprecedented failure to produce a budget, was slow to release its public accounts because it reopened the books – another worrying precedent from a government that should be setting the standard for transparent, reliable and timely financial information.

Massive increases in spending and borrowing by governments in response to the COVID-19 crisis, and ambitions for new social programs and industrial policies in its aftermath, have raised the stakes – and, unfortunately, coincided with some serious backsliding in the transparency and timeliness of financial information.

This annual report card hopes to encourage further progress and limit backsliding. Canadians can get more transparent financial reporting and better fiscal accountability from their governments, if they demand it.

Canada’s federal, provincial and territorial governments loom large in the Canadian economy and in Canadians’ lives. Even before COVID-19 prompted major increases, their budgets and spending estimates for the 2021/22 fiscal year prefigured more than $1 trillion in revenue and expense – around 41 percent of gross domestic product, or more than $26,000 per Canadian.

They use this money to provide services and transfer payments in areas such as health, education, national defence and policing, income support and business subsidies. They tax Canadians’ incomes from work and saving, and they tax spending on most goods and services. Over time, their aggregate expenses have exceeded their revenues, resulting in negative net worth. At the end of the 2020/21 fiscal year, their accumulated deficits totaled $1.4 trillion and, during that year, they paid more than $49 billion in interest.

Taxpayers’ and citizens’ ability to monitor, influence and react to how legislators and officials manage public funds is fundamental to representative government. We need to check that legislators and government officials are acting in the interest of the people they represent, and we need to respond if we conclude that they are acting negligently or in their own interest. Financial reports are key tools for monitoring governments’ performance of their fiduciary duties.

The audited financial statements Canada’s senior governments publish in their public accounts after each fiscal year provide key information. In particular, their statements of operations show their revenues and expenses during the year, and the difference between them: their surpluses or deficits. Their statements of financial position show their assets – both financial assets and capital assets like buildings – and their liabilities. The difference between their assets and liabilities – their net worth – reflects their accumulated surpluses and deficits over time and captures their capacity to provide services now and in the future.

Budgets provide similar information prospectively. Citizens and taxpayers, and the legislators who represent them, can examine the budget a government presents at the start of the fiscal year – notably, its commitments with respect to revenues and expenses and the projected surplus or deficit. The budget should also show the change in net worth that will result from the projected surplus or deficit, so users of the budget will understand the budget’s implications for the government’s capacity to deliver services at the end of the period.

The estimates governments present to legislatures show spending for which the government must obtain legislative approval each year. The estimates’ scope is narrower than the expenses shown in budgets and financial statements – excluding items that do not require votes, such as Crown corporations, and ongoing expenses, such as interest. But they are nevertheless central to legislative control of public money. Legislators should see individual programs in the estimates in the context of the overall plan for revenues and expenses, with its implications for the surplus or deficit and changes in future service capacity.

The C.D. Howe Institute’s annual report on the fiscal accountability of Canada’s senior governments focuses on the relevance, accessibility, reliability and timeliness of these documents. It is not about whether governments spend and tax too much or too little, whether they run surpluses or deficits, or whether their programs succeed or fail. It is about whether Canadians can get the information they need to form opinions on these issues and correct any problems they discover. The letter grades in this report reflect our judgement about whether governments’ budgets, estimates and financial statements let legislators and voters understand governments’ fiscal plans and hold governments to account for fulfilling them.

We put ourselves in the place of an intelligent and motivated but non-expert reader – a legislator, journalist or voter. We ask how readily that reader can find the relevant numbers in each document, and use them to make straightforward comparisons. For example, can the reader compare the revenues and expenses projected and approved by legislators before the start of the year with the revenues and expenses of the prior year? Can the reader compare the revenues, expenses and change in net worth published after year-end with the budget’s projections?

With respect to the budgets and estimates for the 2021/22 fiscal year, and the year-end financial statements for the previous 2020/21 fiscal year – the documents relevant for this report card – the reader would be able to answer such questions about Alberta and Yukon relatively easily. These jurisdictions displayed the relevant numbers early in their documents. They used consistent accounting and aggregation in all their documents. They provided tables that reconciled results with budget intentions, and published in-year updates. They produced timely numbers. They presented their 2021/22 budgets before the start of the fiscal year and presented their main estimates at the same time. Alberta was one of only two senior governments to release its 2020/21 public accounts within ninety days of the end of the fiscal year.

Our reader would have a tougher time with the documents of other governments. Some governments’ budgets, estimates and/or public accounts used inappropriate and inconsistent accounting and aggregation, impeding understanding of the documents and comparisons among them. Some governments buried their consolidated revenues and expenses hundreds of pages into a document or even hid them in separate documents.

Timeliness is uneven among Canada’s senior governments. Some presented budgets after the start of the fiscal year, with money already committed or spent. Some did not present their main estimates simultaneously with their budgets. Some did not release their year-end financial statements until most of the following fiscal year had elapsed, undercutting attempts to compare recent performance against a definitive baseline.

Although the principal focus of this report is the budgets and reports published in the most recent complete fiscal cycle, we have two comments about the past and the future.

Looking back, we are glad to report that, over time, and notwithstanding the federal government’s egregious failure to present a budget in 2020, the quality of the financial information provided by Canada’s senior governments has tended to improve. Two decades ago, none of Canada’s senior governments budgeted and reported consolidated revenues, expenses and surplus or deficits on the same accounting basis; lately, consistent presentations that conform with Public Sector Accounting Standards are normal.

Looking forward, we provide a preview of the scores for the fiscal year 2022/23 budgets and estimates. On this front, the news is mixed. The provinces and territories were generally faster in the most recent budget cycle, with eight senior governments presenting their budgets earlier than last year. Based on the information to date, Alberta is on track for an A+ in our 2023 report card. Saskatchewan and Yukon are on track for grades of A-. Sadly, and significantly, the federal government is on track only for a grade of D+.

A key aim of this annual survey is to limit backsliding and to encourage further progress. The deficiencies we highlight in this report are fixable, as improvements by the leading jurisdictions show. Canadians can get good financial reporting from their governments and they should insist on it.

Bill Robson took office as CEO of the C.D. Howe Institute in July 2006, after serving as the Institute’s Senior Vice President since 2003 and Director of Research from 2000 to 2003. Nicholas Dahir is a Research Assistant at the C.D. Howe Institute.