MARK MACDONALD

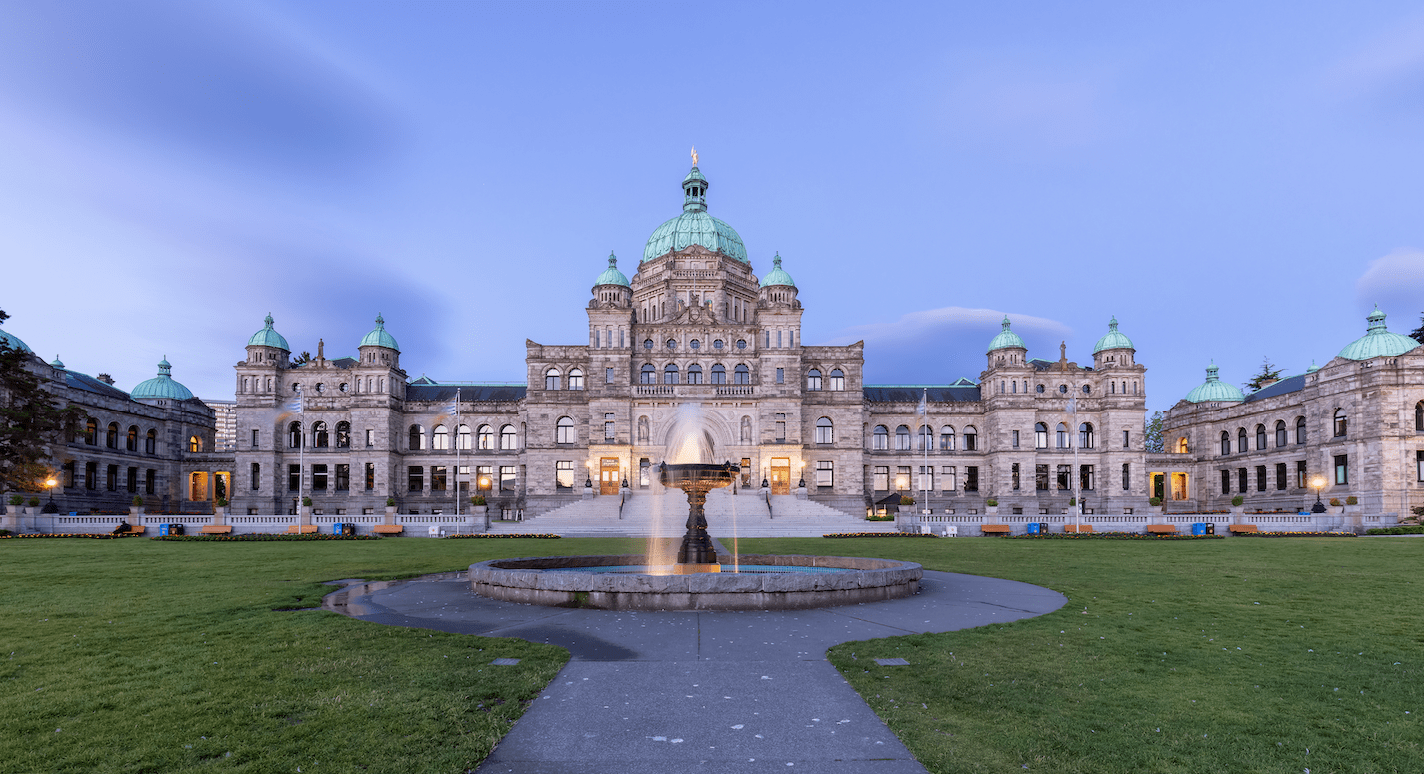

BRITISH COLUMBIA – During hot summers like we’ve just endured, again, temperatures rise – and we’re not just talking about the thermometers.

Conversations swirl about the impacts of global warming/climate change, and how if that isn’t addressed, we are doomed for more of the same. The solution? More taxes, of course, to fight it. And voila, extra justification for carbon taxes, to somehow make people feel good for paying more at the gas pump. . .something akin to a cleansing of the conscience.

Isn’t it amazing that with all the technology used in weather predicting, the best experts can barely tell us what the weather is going to be like four days out. Yet they are absolutely convinced that the weather is going to be such-and-such in 100 years.

With all of this conversation, and knowing that nature is powerful and most often uncontrollable despite the best of human intentions, we never stop to look at mitigation and preparation in order to protect the environment, our prized possessions, and ourselves, from hot weather – the precursor to forest fires which plague our province with increasing frequency.

Why not ask the question: Is there anything we can do to reduce forest fires and drought – and if not, at least prepare better for them? Yes we can.

More people are beginning to ask aloud about the impact of provincial forest policies, much of those driven by ideologies that make removal of any kind to be anathema. For decades now, the government – echoed by mainstream media – has demonized clear cutting of forests. Mostly it’s in favour of selective harvesting.

Yet when the experts get involved with fighting fires, what do they effectively use? Clear cuts – although they’re not called that, of course. They create “fire barriers”, which is where swaths of trees are cut down so that flames can’t jump across the chasm between what is already burning and what could be next.

Selective logging sounds good in theory, but in reality, what it does is encourage logging operations to choose the best wood standing in the forest and harvest that. What is left is deficient, often-diseased, broken trees that become like stands of kindling, ready to explode at the first spark.

When BC was plagued with pine beetles that attacked trees, the government was perpetually slow dealing with the problem. Which left multiplied acres of dried pine wood, laced with its natural resins that act like gasoline during a fire.

There is zero likelihood that citizens would accept a return to the “dreaded clear cut” method of logging. But perhaps if it was re-packaged as creating fire barriers, might people be more accepting?

With the desire to live amongst oxygen-producing trees, urban sprawl has gravitated outwards into nature, and in most cases, there is no fire barrier at all. If a fire were to start in the forest, it’s literally in the backyards of subdivisions, leaving no chance for escape.

What is uglier? Forests that have been clear cut, or the aftermath of forest fires?

Other jurisdictions are starting to be more pro-active in this regard.

In a recent article on the state of fires in California, James Johnston, a forest management and wildfire expert at Oregon State University, stated the world needs to “stop waiting for vast tracts of the continent to catch fire before thinking about how to deal with the problem.”

“It’s true that the only way to fight fire is with fire,” Johnston said. “We don’t have a choice about whether to have a fire, but we do have some choices about where and when.”

Another story in the Powell River Peak cited the successes occurring in Australia, where traditional Indigenous burning practices of setting fire to the land in the right way at the right way at the right time can ramp up biodiversity.

University of British Columbia researcher Kira Hoffman told Glacier Media “Overwhelmingly, Indigenous fire stewardship and cultural burning practices almost always benefit or enhance biodiversity. . .across all scales.

“If we had more cultural burning, we’d have a very different looking landscape. . .a lot more open, lot less dead and dying trees on the ground – man forests would have trees of different ages,” Hoffman states. “It doesn’t stop fire from coming in, but it can slow them down.”

Another unpopular issue is the building of reservoirs. Isn’t it amazing that Vancouver Island, deluged with rain for over half the year, has water shortages in the summer? Rain pelts down throughout the winter and much of the spring, joining rivers and creeks as they run right into the ocean. We have plenty of rain and water, just not when we need it. Why, then, aren’t we storing more it for use in warmer weather, including for fighting fires and irrigation?

Are these ultimate solutions? Perhaps not. But they should at least become part of conversations within the provincial resource ministries to help prepare for disasters beforehand instead of sighing and blaming the weather while the province burns.

Mark MacDonald is President of Communication Ink Media & Public Relations Ltd. and can be reached at mark@communicationink.ca