JOCK FINLAYSON

By Jock Finlayson, ICBA Chief Economist

BRITISH COLUMBIA – The 2024 federal budget unveiled dozens of new initiatives intended to address Canada’s unfolding housing affordability and supply crisis. Never before have Canadian politicians been so seized with housing-related issues.

At the heart of the problem is a large and still-growing gap between the country’s available housing stock and the number of new Canadian households being formed. New households emerge due to in-migration, young adults entering the housing market (usually to rent), divorces/separations, and other factors. In the Canadian context, immigration-driven population growth is the principal driver of new household formation. As of 2023, Canada had more than 16 million households, up from just under 12 million in 2001 and around 13.75 million in 2011. Note that each household requires a dwelling unit.

A recent RBC Economics report estimates that Canada gained 933,500 additional households between 2019 and 2023, while the housing stock rose by 763,500. The Parliamentary Budget Officer reports that even in the pre-pandemic period from 2015 to 2019, there was a persistent discrepancy between household formation and net additions to the housing stock (after accounting for new completions plus conversions and demolitions). For example, the PBO found that Canada added 460,000 net new households last year, while home completions reached 242,000. And two years earlier, in 2021, the PBO estimates that Canada would have had 631,000 more households “if attainable housing options had existed.” That number presumably would be considerably higher today given rapid population growth over 2022-23 coupled with a drop in housing starts.

Stated differently, Canada has been experiencing “suppressed household formation” owing to the insufficiency of the housing stock and the slow pace at which new supply has been brought to market – especially at a time of significant population growth. In practice, this translates into more young adults living with their parents for longer periods, multiple roommates cohabiting in small dwelling units, more people “couch-surfing”, etc.

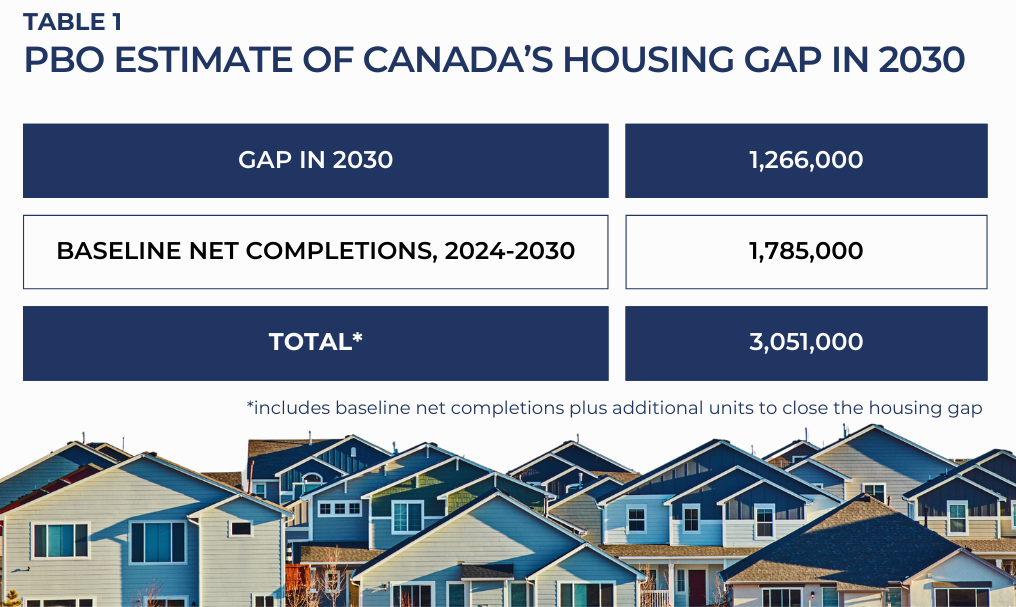

Looking at the existing housing stock and using Statistics Canada’s main population growth forecast, the PBO concludes that Canada needs roughly another 1.3 million housing units, over and above the projected baseline addition to supply, to eliminate the housing gap by 2030. Table 1 below summarizes the PBO’s calculations:

Recent Developments

There are lots of moving parts as we try to understand where Canadian housing policy and housing markets are headed. Governments are stepping forward with a hitherto unimaginable array of programs and initiatives – amounting to billions of dollars of incremental public spending – to help develop new housing, preserve existing rental stock, discourage speculation, and clamp down on the short-term rental market. Over time, this policy mix should result in more dwelling units being built, including a larger rental housing stock. But making significant headway will take at least several years; in the near-term, we are unlikely to see a surge in housing starts or completions.

What will make a difference in the short-term is the federal government’s decision to cut back on immigration. Because immigration is responsible for almost 100% of Canada’s population growth, admitting fewer newcomers will translate into smaller net increases in the size of the population, right away. In the past few months, Ottawa has announced a freeze on permanent immigration and a substantial curtailment in the number of “non-permanent” immigrants who will be permitted to come to Canada, effective in mid-2024. This has been accompanied by a quantitative target to scale back the “non-permanent” resident population from 6.5% of the overall Canadian population today to 5% in the next couple of years.

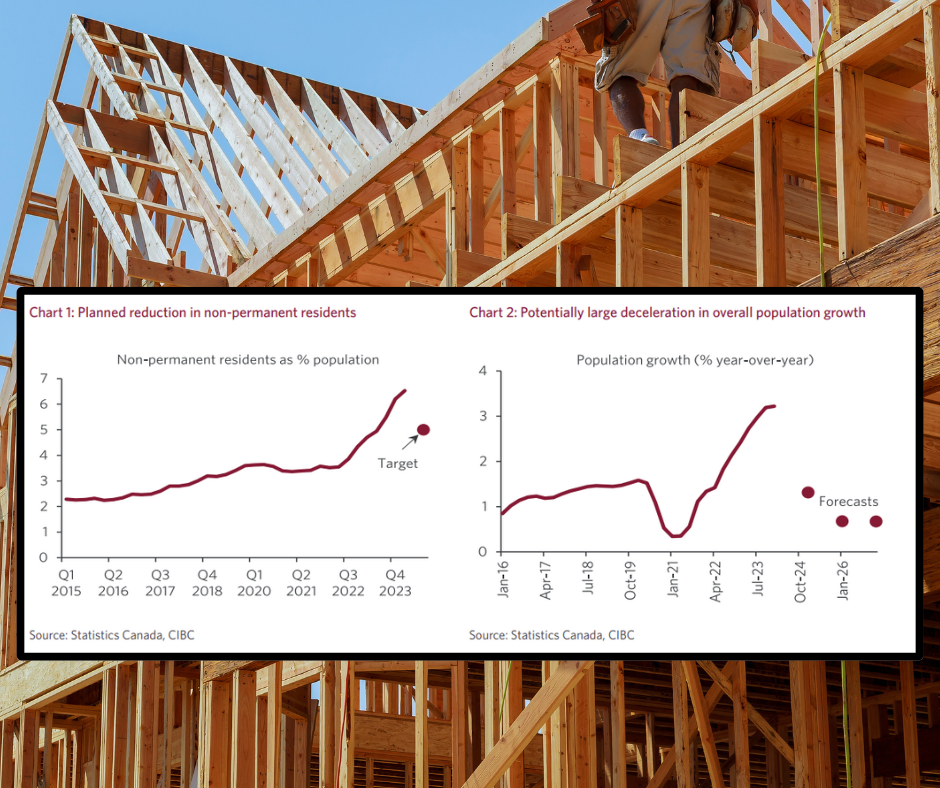

CIBC Economics has analyzed the impact of Ottawa’s immigration policy announcements on Canadian housing and labour markets. As shown in Charts 1 and 2, these changes portend a very material slowing in population growth.

Chart 1 captures the rising share of the population accounted for by non-permanent residents (NPRs) since 2015, along with the lower target announced by the federal government several weeks ago.

Chart 2 depicts Canada’s rapid population growth since 2021 and provides (with the dots) different forecasts for population growth in 2024-26, based on recent federal policy shifts. From more than 3% in 2023, Canada’s annual population growth rate is expected to downshift to 1% or less in 2025-26. This points to a marked deceleration in new household formation and, therefore, to less demand for housing, compared to what Canada has experienced in the last few years. As CIBC notes, fewer immigrants and fewer new households should “help to ease some of the most acute pressure” being felt in Canadian housing markets, particularly rental markets.

Thus, to the extent we do observe a visible softening in the overall demand for housing over 2024-26, it will reflect the actions the federal government is taking on the immigration front, more so than the effects of the various housing policy measures that have been adopted by Ottawa and the provinces since 2022.

Source: IBCA