JOCK FINLAYSON

BRITISH COLUMBIA – Any lingering doubts as to whether government is now the principal “growth industry” in British Columbia can be safely set aside after last week’s provincial budget. Among the highlights – and lowlights – that caught my eye:

- the largest operating deficits in B.C.’s history over the next three years – even bigger than at the worst point of the 2020-21 COVID shock;

- substantial increases in program spending, along with fast-rising debt-servicing costs;

- a further expansion of the NDP government’s already ambitious capital spending plan; and,

- a vertiginous increase in the accumulated public sector debt over the forecast horizon.

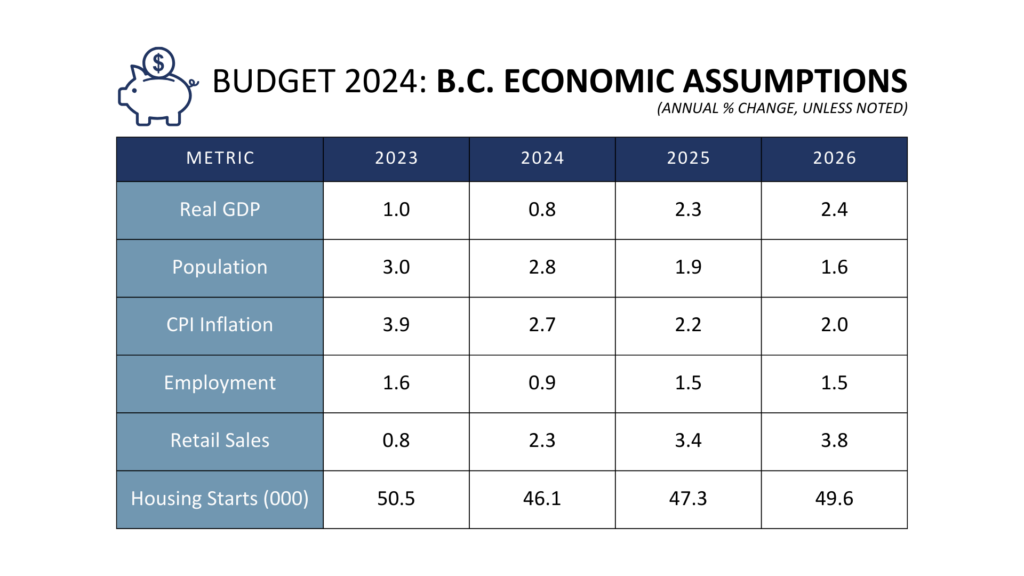

The economic backdrop for the 2024 budget can only be described as subdued. After posting solid real GDP growth in 2022, the province’s economy sharply downshifted – as did Canada’s – last year, with annual growth coming in at a tepid 1%. For 2024, the budget predicts growth will slip further to 0.8% – and even that uninspiring number is more optimistic than the current private sector consensus of 0.5%. The labour market will continue to soften as many B.C. businesses slow hiring or trim their payrolls.

While the budget was silent on the subject, the reality is that job gains in B.C. have been heavily concentrated in the sprawling public sector – government itself, plus the health care, education and social service sectors. From 2019 to 2023, public sector employment soared by more than 20%, while private sector payroll jobs inched ahead by a meagre 3%. This unbalanced picture is neither desirable nor fiscally sustainable. We believe it points to underlying problems in the wider business climate. Nonetheless, the 2024 budget signals a doubling down on the NDP’s “government first” economic growth strategy.

The budget does contain a few measures that will assist businesses, including a temporary reduction in electricity costs and an increase in the threshold for levying the Employer Health Tax (EHT), along with some adjustments to the carbon pricing regime that applies to energy-intensive, export-oriented industries. But these are small steps considering that the province has imposed more than $6.5 billion in tax and fee increases on business in recent years, according to estimates from the Greater Vancouver Board of Trade. Moreover, another significant tax hike is coming on April 1, when the B.C. carbon tax increases again from $65 to $80 per tonne of emissions.

B.C.’s population has been expanding faster than overall economic output, resulting in a serial erosion of “personal prosperity” – defined as the value of real GDP per person. This key indicator of economic well-being decreased by roughly 2% last year and will put in a repeat performance in 2024. Nor can a further decline be ruled out in 2025.

Table 1 summarizes the main economic assumptions underpinning the budget. We believe the B.C. government’s population growth projections beyond 2024 are “optimistic,” in that they underestimate the magnitude of likely international in-migration based on the aggressive immigration targets adopted by the federal government. This means per capita GDP growth could continue to disappoint even beyond 2024, underscoring the risk of a lengthy period of stagnating/falling living standards.

For the coming fiscal year (beginning April 1, 2024), the government is planning to boost spending by more than 8% – roughly three times the inflation rate – with expenditures climbing across almost all ministries. A major driver of this is higher payroll costs, due in large part to new collective agreements negotiated over the past two years. Around half of B.C. government program spending ultimately is absorbed into payroll costs across the broad public sector. These costs will be escalating steadily over the forecast horizon.

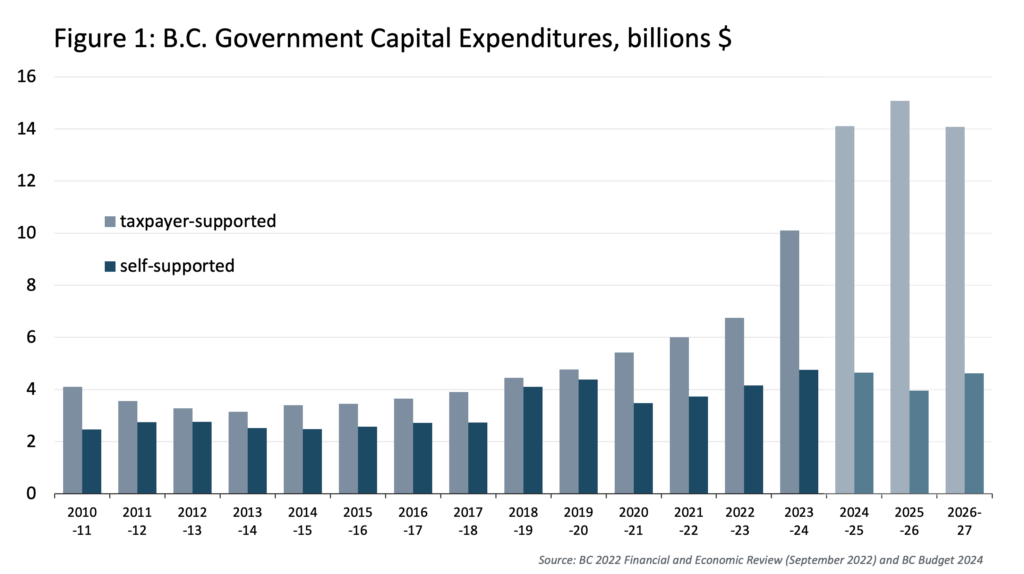

With a growing populating and an aging (and inadequate) infrastructure stock, the province is right to commit to an ambitious capital plan that will see total capital expenditures increase sharply in the next few years (Figure 1). Hefty capital outlays are the most important factor pushing up the accumulated taxpayer-supported debt and the net debt/GDP ratio, with the latter on course to reach 21% in 2024/25 (up from 17.6% this year) and a record 27.5% by 2026/27. A decade ago, the net debt/GDP ratio was under 15%. The soaring debt is due to borrowing to pay for capital projects and projected combined operating deficits totaling $28 billion from 2023/24 through 2026/27.

Absent an actual recession, we see no reason why the province should be running operating deficits. And while ICBA supports borrowing to fund capital spending on roads, bridges, hospitals and other long-lived assets, the NDP’s ill-advised “Community Benefits” model for procuring projects is adding hundreds of millions of dollars in unnecessary costs every year to build new and refurbish existing infrastructure and other capital assets. A rethink of the government’s policy in this area is urgently needed.

What Lies Ahead…

When it comes to provincial fiscal policy, there are more shoes to drop as the date of the next election draws nearer. The NDP is likely to unveil an election platform featuring additional costly promises; the opposition parties may follow a similar path. If so, this will put more pressure on the province’s public finances going forward. British Columbia can’t continue to run sizable operating deficits with no end in sight. And the jaw-dropping rise in the debt teed up for 2024/25 certainly can’t be replicated year-after-year. All of this points to the very real prospect of significant tax hikes, particularly under a re-elected NDP administration, as well as a probable downgrading of B.C.’s still solid credit rating within the next 6-12 months.

While it includes a handful of measures to address the cost-of-living crisis and the financial challenges facing many B.C. businesses, Budget 2024 fails to pass the test of fiscal responsibility. Nor does it do much to create conditions that will support a thriving, growing, and innovative private sector. Provincial policymakers seem preoccupied with enlarging the public sector and extending the tentacles of political influence and control into more domains of economic and social life. They have forgotten a basic fact: even in 2024, B.C. remains a market-based economy, one where wealth creation overwhelmingly comes from the private sector, where four-fifths of all jobs are in the business community, and where more than 90% of export earnings are attributable to commercial and industrial activity. Contrary to the prevailing wisdom in Victoria, expanding the size and reach of the public sector is not the secret sauce for durable economic success.

By Jock Finlayson, ICBA Chief Economist